The Threads Behind Embroidering Palestine: Rachel Dedman and Kaat Debo in Conversation

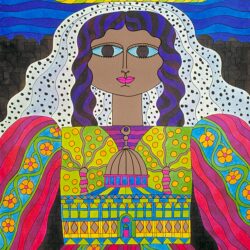

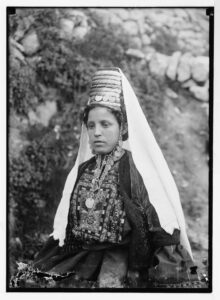

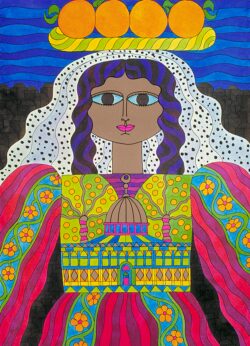

Embroidering Palestine explores Palestinian embroidery and dress through the lenses of nature, splendour, power and change. Embroidery, called tatreez in Arabic, is one of Palestine’s most important cultural practices. More than a craft, tatreez in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was a visual language shared by women, reflecting identity and origins through every stitch. MoMu sat down with guest curator Rachel Dedman and director Kaat Debo to unravel the threads behind the exhibition.

What inspired MoMu to dedicate an exhibition to Palestinian embroidery?

KAAT DEBO: At MoMu, we approach fashion as a cultural phenomenon with social, historical and political dimensions. This exhibition fits perfectly within that vision. By showcasing Palestinian embroidery, we want to highlight the rich textile traditions of Palestine and draw attention to the role of fashion as an expression of identity, community and resilience. Fashion is a lens through which we can view the world from different perspectives, and Palestinian embroidery is a powerful example of that.

This is your first time working together. How did this collaboration come about?

KAAT DEBO: We first encountered Rachel’s work through her publications on Palestinian embroidery and the remarkable exhibition Material Power: Palestinian Embroidery she curated in 2023 for Kettle’s Yard and The Whitworth. That show was the first major exhibition on Palestinian embroidery in the UK in over 30 years, and it really impressed us.

RACHEL DEDMAN: It was wonderful to receive MoMu’s invitation. Since 2019, I’ve been Curator of Contemporary Art from the Middle East at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and Palestinian textile traditions have been a focus of my work for many years. For me, this exhibition is an opportunity to bring the rich stories of tatreez to a new audience in Antwerp.

Can you tell us more about the themes of the exhibition?

RACHEL DEDMAN: The theme Nature opens the exhibition by celebrating the deep connection tatreez has to the land in Palestine. Embroidery was traditionally the craft of rural women, embedded in their lives in agriculture, with motifs inspired by flora, fauna and daily life. Every fibre of a historical garment reflects this connection to the natural world: a strand of linen might have been harvested in the Galilee, woven in Gaza, dyed with locally-grown indigo.

The section titled Splendour looks at the use of gold, silver and mother-of-pearl on clothing and jewellery, marvelling at the extraordinary craftsmanship of Palestinian artisans and the ways clothing reflected wealth and status.

The theme of Change feels particularly pertinent because, like all fashion, tatreez was ever-evolving. Clothing from Palestine bears the marks of political and social change in Palestine – shifting norms around dress during the British Mandate period (1918-48), or the presence of new textiles and thread. Alongside the ways colonial rule and occupation have impacted dress, we also look at how the emotional landscape of a woman’s life – love, grief, motherhood – are written into her clothing, offering traces for us to unfold a human history of place. The final section, Power, explores the talismanic protection that Palestinian embroidery and jewellery were perceived to hold over the body. Highlighting the role of dress during the uprisings of the First Intifada, this section speaks to the transformation of tatreez into a practice of resistance against erasure and occupation, looking at both embroidery and the keffiyeh as textiles embodying global Palestinian solidarity.

We took a thematic approach to the exhibition so that we could embed the historical and the contemporary side-by-side, delving into ideas that connect Palestinian embroiderers, designers, artists and makers across time.

How does the exhibition engage with the politics of Palestinian fashion?

RACHEL DEDMAN: The objects on display date from the late nineteenth century up to the present day, so the show addresses important political milestones in this period, for example the Nakba (‘catastrophe’ in Arabic) of 1948, which saw the displacement and dispossession of 750,000 Palestinians and the destruction of hundreds of Palestinian villages. We talk about the effects of British colonialism on dress between 1918 and 1948, and address the politicisation of tatreez and its role in symbolic and active resistance to Palestine’s occupation in the second half of the twentieth century. I would argue that heritage is inherently political, particularly at a time when Palestinian cultural sites and collections are being deliberately destroyed by the Israeli military in Gaza and the West Bank. For all the contemporary designers we are working with, too, fashion is political. To help visitors navigate the context of the exhibition, we have included a glossary explaining key terms and giving some greater insight into milestone moments in Palestine.

What can visitors expect from the exhibition?

RACHEL DEDMAN: We’re fortunate to have borrowed important historical objects from renowned collections, including Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac in Paris, the Textile Research Centre in Leiden, and the Wereldmuseum in the Netherlands, and the majority of archival material comes from the Palestinian Museum’s extraordinary Digital Archive. At the same time, the exhibition highlights a new generation of designers, such as Ayham Hassan, Reemami, Studio Nazzal and Zeid Hijazi, who are evolving the traditions they inherit and giving tatreez new meaning in the present.

KAAT DEBO: We’re also introducing talks, events and workshops together with artists, curators and researchers. Our aim is to create an open, respectful space for dialogue and reflection.

Embroidering Palestine is on view from 13 December2025 through 7 June 2026. More info and tickets available here