Antwerp Pride 2022: Gender Boundaries Are to Be Flouted

From August 10 through August 14, Pride is taking over the city of Antwerp to commemorate and celebrate the LGBTQIA+ community’s long journey towards acceptance and equal opportunities. In honour of this year’s edition, we are illuminating the rich history of queer fashion by zooming in on women who defy conservative societal expectations and express their sexuality and gender identity through their choice of clothing.

Since Antiquity, theoretical arguments have been formulated to justify the need for distinctive looks between men and women, to ensure social and moral order. Such thoughts assert a duality between the two main recognised genders: female and male. Cross-dressing — or the wearing of clothing typical of one’s opposite sex — is a way to challenge this duality.

In a time period marked by latent homophobia, the French comedian Mademoiselle Raucourt (1756-1815) publicly appeared with her female partners. She was sometimes called the “Chief Priestess of Lesbos” and her position as a well-known actress and member of the Comédie-Française enabled her to come to terms with her sexuality and personality. She was known for regularly dressing up as a man when going out and, moreover, she also wrote the play Henriette, in which the protagonist disguises herself as a soldier. Raucourt herself played Henriette on stage and was acclaimed for her performance. However, due to her provocative behaviour she eventually had to flee France for several years. Later, upon her death, her body was not allowed to enter the church on the day of her funeral. Nevertheless, her character became a mythical example of risk-taking and self-affirmation.

Cross-dressing does not only imply a manipulation of sartorial codes but also of habits. Both are combined to undermine the respective stereotypes of male and female genders and to threaten a strict and consensual conception of masculinity vs. femininity. For example, the French writer George Sand (1804-76) — born Amantine Aurore Lucile Dupin de Francueil — used to publicly dress up in men’s clothing. She would noticeably wear trousers, which was illegal for a woman at the time. By doing so, she pinpointed the practicality of masculine fashion in contradiction with feminine garments, which often restricted body and movements. With her outfits, she revealed certain power dynamics and this critical way of thinking was also reflected in her writings. Shifts in gender codes can be as subtle as extravagant, as daily as occasional, but they all come from a similar wish to affirm one’s non-conformity to established social order.

In addition to public figures who stood out for their values, certain items of clothing also enabled groups of people to rally behind a common cause — for example the cotton t-shirt. Initially, t-shirts were primarily worn by soldiers, workers and bachelors, but by the 50s they had become more widespread and grew into a fashionable item, partly due to the influence of cinema. Subsequently, from the 60s onwards, the t-shirt turned into a powerful political tool as it was cheap, not gender-specific, and, most of all, customisable.

For example, in 1970, the Lavender Menace, a collective of lesbian radical feminists, dyed and silkscreened t-shirts with their slogan for a non-violent protest organised during the Second Congress to Unite Women. As a slogan, the collective reappropriated the expression “Lavender Menace”, employed in 1969 by Betty Friedan, the then president of the National Organization for Women. In her speech, Friedan had spoken out against the association of her organisation with the fight for lesbian rights, as she believed this to be damaging to the organisation’s primary objective. The Lavender Menace t-shirts functioned as a reaction to these views and affirmed their common fight and their power as a group.

And if text was always part of a protest landscape — often marked on boards —, the introduction of slogans and shirts freed the protestors’ moves and let them strongly embody their cause. As such, these slogans could also permeate daily landscapes and not only be bound to the context of protests. This silent way to stand for a cause never ceased to exist and printed t-shirts accompanied many social fights since the second half of the 20th century. Furthermore, purple is still nowadays the symbolic colour used by the lesbian community.

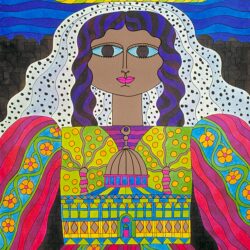

The revendication of queer culture is also particularly known for using extravagance, disguise and artifice to perform identities outside of the norm and refuse standardisation. Fashion is thus at the core of the perpetual redefinition of what female or male bodies are — a conservative boundary that contemporary debate intends to flout and question.

For more info on Antwerp Pride, please see antwerppride.com

For suggested further reading, we highly recommend ‘A Queer History of Fashion: From the Closet to the Catwalk’ by Valerie Steele, available for consultation at the MoMu Library